Happy birthday, Regiment of Traitors!

/On this day in 1813, the Canadian Volunteers mustered and were reviewed for the first time. To many who don't know the history of the War of 1812, the name "Canadian Volunteers" is misleading. These Canadians were, in fact, fighting on the side of the American invaders. If captured, they would have been treated as traitors to the Crown.

On July 17, 1813, the Inspector General of the U.S. army reviewed the troops and reported to General Boyd and to Secretary of War Armstrong that the troops were "able-bodied men and well-disposed to joining us against the enemy." The "enemy," of course, included their former friends, neighbours and family members serving in the militia units of Upper Canada. This was a civil war.

The commanding officer, Joseph Willcocks -- a well-known politician and newspaper editor before the war -- had been commissioned as a Major by General Dearborn a week before. The other officers included: Captain Gideon Frisbee; First Lieutenant Robert Huggins; Second Lieutenant Abraham Cutter; Ensign Samuel Jackson Junior; Adjutant Joshua B. Totman; Quartermaster Samuel Jackson Senior; Commissary William Wallace; and Surgeon John Dorman.

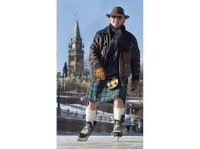

Photo: Rolf Gollin

On that day, the strength of the "regiment" was 44 rank and file, in addition to the nine officers. It was a small acorn from which Willcocks hoped that a mighty oak would grow -- he expected that he would eventually raise 600-800 men. But during the war, a total of only 164 men served in the unit. In other words, the regiment was more the size of a company, commanded by a Major, who was later promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel.

Photo: Rolf Gollin

In his unpublished master's thesis, "Joseph Willcocks and the Canadian Volunteers: An Account of Political Disaffection in Upper Canada During the War of 1812," submitted to the Department of History at Carleton University in 1982, Donald Graves analyzed the muster rolls to determine some of the background of the men who fought for the other side. From the birthplace of those who can be identified, Graves concludes that the majority of Canadian Volunteers were born in the United States and emigrated to Canada before the war. The next highest percentage come from Ireland. A majority of them (60%) resided in the Niagara District of Upper Canada. (It must be emphasized that these results are based on only a sample of the Canadian Volunteers for whom records are available.)

Photo: Rolf Gollin

Only 13% of the Canadian Volunteers owned property. Graves points out that this indicates low socio-economic stratus in pre-war Upper Canada. On the other hand, three of the officers possessed more than 400 acres.

In spite of their small numbers, the Canadian Volunteers proved to be an effective fighting force during the war. On the one hand, their knowledge of the local terrain and population was invaluable to the American command. In November 2013, this led to them being assigned responsibilities for policing the occupied portions of the Niagara Peninsula. They appear to have carried this out with a spirit of vengeance that climaxed, on December 10, 2013, with the burning of Newark (Niagara-on-the-Lake.) Modern-day visitors to NOTL are told the story of how "the Americans" set the torch to one of the most prosperous pre-war communities in Upper Canada. Actually, it was done by the Canadian Volunteers.

In combat they proved to be fierce fighters, distinguishing themselves in the savage fighting in the Niagara peninsula and the retreat to Buffalo. Perhaps their ferocity as soldiers came from the knowledge that they could not surrender and survive.

Photo: Rolf Gollin

During the Ancaster Assizes of July 2014, several Canadians who had been captured fighting for the U.S. were tried and executed. None of them were Canadian Volunteers, but the hangings sent a powerful signal of what they might expect. Joe Willcocks and other leaders of the unit were tried in absentia and sentenced to death and had their property forfeited to the Crown.

One of the features that I find interesting is the absence of information about whether any of them ever surrendered. I assume that if they did, they would be quickly and quietly dispatched with no records kept.

Why did 164 residents of Upper Canada join the American army rather than defend against the invasion? Some historians think they were motivated by opportunism -- in the spring of 1813, it looked as if the Americans were going to win the war, and they wanted to get in on the spoils of the victors.

Photo: Rolf Gollin

But by July 17, the course of the war was far less certain. The Americans had been stopped at Stoney Creek, a large force had been surrounded and had surrendered at Beaverdams, and nine days previously a small American force had been massacred on the outskirts of Newark at Ball's Farm.

Instead of opportunism, I tend to see some idealism in the decision made by those who joined the Canadian Volunteers. They were democrats at at time when "democracy" was considered by the ruling establishment in Upper Canada to be a sinister and destabilizing influence. (Think how many North Americans regarded "communism" during the Cold War, and you get the picture.) Many of the ideas they believed in would be implemented by later generations -- public schools, responsible government, opening up reserved land for settlement. They wanted "liberty" the way their American neighbours understood the term.

photo: rOLF gOLLIN

Many in Upper Canadians took pride in their "liberty" but it was a British notion of liberty that emphasized constitutional monarchy; democrats, on the other hand, wanted a system more like the situation in the United States where voters had more control over public policies, institutions and representation.

To exacerbate the different notions of "liberty," the governing elites of Upper Canada tended to include a small group of authoritarian, venal and in some cases corrupt insiders who would, in the coming decades, become known as the Family Compact. The democrats, whigs, ordinary farmers and tradespeople had reason to think that their lives and fortunes might improve as part of the Republic to the south. It's surprising that more of them didn't join the Canadian Volunteers. Most Upper Canadians just wanted to stay out of the war.

Photo: Rolf Gollin

All of this forms the background -- and the narrative spine -- for the Jake and Eli stories. The current work-in-progress, tentatively titled The Company of Traitors, will take the story from July to December 1813.