Neuf Thermidor -- and politics

/On this day in 1794, one of the cataclysmic revolutions in Western history came to an end in a day that has left its name in the history books, much has 9/11 has been etched in our psyche. It's called Neuf Thermidor.

Maximilien Robespierre overthrown in the Convention.

What's a Thermidor? In their efforts to build the world anew, based on reason, the French Revolutionaries created a new system for measurement, based upon units of ten -- the metric system. They also tried to apply reason to a new way to measure time, based upon ten-day weeks, built around months named for the seasons. This month was known as Thermidor in the revolutionary calendar -- the month of heat.

As poetic as the names of the new months were (Germinal, Prairial, Brumaire...) France's revolutionary calendar failed to catch on as well as the rest of the metric system. It failed to take into account that different countries experience different climates. Try to convince someone in Brazil that December should be called Nivose -- the month of snow!

Lobster Thermidor

But the word Thermidor remains in our vocabulary because of a lobster dish named after it -- named, in fact, in honour of the events that occurred on the 9th day of that month, but July 27 by our calendar. It's synonymous with overthrowing a revolution, putting an end to social upheaval and political terror, and the restoration of right-wing government -- this, even though those who staged the coup to bring down the government were even more radical terrorists.

The execution of Robespierre.

It was on this day that Maximilien Robespierre and the Committee of Pubic Safety were overthrown by elements within the Convention (the political assembly of revolutionary France.) The sans-culottes of Paris who, for years, had provided the muscle that enabled Robespierre and his fellow Jacobins to control the political agenda, failed to come out to save him. They were tired of the excesses of the Reign of Terror that had seen some 17,000 French executed as "enemies of the Revolution" in less than two years.

The sans culottes -- "brown shirts" of the French Revolution.

It is argued by some that the French Revolution continued under the Directory that followed Robespierre and under Napoleon who ruled France until 1815, but on July 27, 1794, it was as if a fever had broken. The Terror ended. It left a legacy that remains to this day when political authorities use force, fear and mass executions to try to build a perfect world.

Maximilien Robespierre, French revolutionary.

In understanding the War of 1812 and the role of Joe Willcocks and the Canadian Volunteers, it is useful to keep 9 Thermidor and the Terror in mind. The date may be remote and obscure for us, but for people in Upper Canada, the French Revolution continued to resonate.

Think about it: by 1812, the Reign of Terror was only 18 years in the past. The equivalent today is 1998. The Good Friday Accord was signed, bringing peace to Northern Ireland. The euro was adopted as the single currency of the European Union. Terrorists bombed U.S. embassies in Tanzania and Kenya. In Eastern Canada, we were hit by an ice storm that left entire cities without electricity in sub-Arctic temperatures. For me, none of this seems very long ago!

The ice storm, 1998.

And the French Revolution remained a living legacy of those who pushed ahead their own social and political agendas, whether they were Tories or Whigs, Federalists or Republicans. When assessing the motivations of one's friends or enemies, the context was the not-too-distant memory of the French Revolution.

Thomas Jefferson, American radical revolutionary.

The idea that you needed terror and blood to help nurture a better world was taking root on both sides of the Atlantic. Thomas Jefferson himself argued in a letter to John Adams that "the tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and of tyrants." For John Adams, a Federalist, this must have seemed an inflammatory and dangerous idea, but it was not outside the rhetorical framework with which the Left of the day described the need for social upheaval.

For the Right, including the established families of Upper Canada that would, in the next decades, evolve into the Family Compact, those who espoused what we today might call "progressive" ideas were as good as fomenting revolution, and represented a slippery slope to outright Jacobinism.

John Strachan, Canadian Tory.

This is a useful way to try to understand Joe Willcocks and the Canadian Volunteers. They have been largely forgotten by history, and when remembered at all they are seen as traitors: Canadians who fought -- and fought well -- for the American army. In the context of their day, they were indeed traitors but they were something equally dangerous to the political authorities of the time: they were proponents of radical ideas that, if left unchecked, would lead to the kind of bloodbath Robespierre had overseen in France.

John Beverley Robinson, scion of the Family Compact.

As for Willcocks and his soldiers, there may have been a degree of opportunism among their motivations -- likely a great deal of it. But they were also Whigs trying to protect liberty in a colony dominated by Tories. Their ideas for social and political reform -- new roads, schools for everyone, an executive accountable to an elected assembly -- were thwarted at every turn by those who wielded power. Rather than give in to a jumped-up aristocracy based upon the ability to ingratiate one's self to the governor sent from England, Willcocks and others thought Canada would be better off as part of a republic. It was a dangerous idea at the time, and it was treasonous.

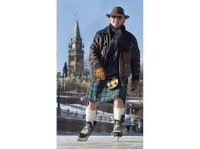

The political debate continues to burn.

These are old feuds, old fights, but people were willing to die for them. In this election year in the United States, in the week when the media abuzz about the Democrat and Republican national conventions, it's perhaps easier to understand the passions that political ideas can arouse. The vitriol and hostility between those who favour Clinton and Trump give us some kind of an idea of how inflamed the debate became in 1812 when such different political futures were presented to the people of Upper Canada.

It's not surprising that some of them turned to American ideas and American institutions as a better way forward. It's perhaps more surprising that more Canadians didn't join Willcocks -- but that, as they say, is another story!