John Norton -- recognition at last!

/I wish I could have been there! Last Sunday, at the highest point of the park at the top of Queenston Heights where a decisive battle was fought 204 years ago, a monument was unveiled honouring the warriors from First Nations who played such a pivotal role in the War of 1812. Among the figures portrayed in the monument is John Norton (his Mohawk name was Teyoninhokarawenone), one of the most intriguing people in Canada's history.

The memorial is designed as a place to gather and remember. When the plans for building it were announced in 2014, the news coverage emphasized the collaboration between Toronto artist Rom Ridout's vision of a Memory Circle and Six Nations artist Raymond Skye's castings of the First Nations war chiefs.

The memorial highlights Norton and his adoptive-brother, John Brant, who led a band of about 80 Haudenosaunee warriors from Grand River. From the woods, they pinned down an American army under the field command of Colonel Winfield Scott. The Americans had crossed the river that morning and had, it was thought, decisively beaten General Brock. The Six Nations warriors pinned them down long enough for a larger British army to march from Fort George. The warriors' war cries unnerved the American soldiers so badly that reinforcements refused to cross the river. The role of Norton and Brant and the Iroquois warriors was recently highlighted in a Heritage Minute.

I imagined that same episode when the Six Nations warriors must determine whether to fight when I wrote A Hanging Offence. In fact, when I first saw the Heritage Minute, it reminded me very much of the scene in which a cold and frightened Jacob Gibson, fleeing from the battle where he has seen his General Brock killed, comes across Norton and the Haudenosaunee.

Norton figures large again in Blood Oath, where he plays a pivotal role both at the Battle of Fort George and the Battle of Beaver Dams. What we don't see in the book (because this part of the story is told from Eli's perspective) is that Norton was also instrumental at the British camp at Burlington Heights in keeping the Six Nations from turning against the British during the darkest days of the war. If not for John Norton -- his tactical brilliance at Queenston Heights and his political acumen at Burlington Heights -- I doubt whether Canada would be a country today.

And yet, he is virtually unknown. I hope the monument and the Heritage Minute will help change that. Professor Carl Benn of Ryerson University, who edited the reprint of the Champlain Society's publication of Norton's journal, has told me he is working on a biography of John Norton. Professor Benn's The Iroquois in the War of 1812 remains one of the best works on the War of 1812, in my opinion, and was of immense value in researching the Jake and Eli stories.

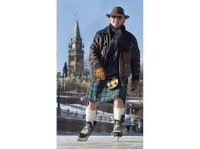

One of the features that makes John Norton so intriguing a historical figure is that he fit so effortlessly is two different worlds. His mother was Scottish; his father, Cherokee. He was raised in Scotland to be a gentleman and scholar and was perfectly comfortable in the salons of the greatest aristocrats of his day. And at the same time, he had also completely absorbed the culture of his father so that, when he came to North America, he was accepted by the Iroquois and adopted as a son by no less than Joseph Brant, the Mohawk war chief.

Norton himself became a war chief in turn, along with his adoptive half-brother, John Brant. But the most intriguing aspect of Norton's biculturalism, for me, was not the manner in which he could be accepted as a leader in two such separate cultures, but the way in which his brain could apparently function in two different media worlds.

From his mother's side, he wrote very well and his diaries and memoirs stand out as important records of the world of North America in his day. From his father's side, he had the capacity for memory that comes from a culture that does not write things down -- and therefore you must remember. Every conversation. Every river bend. Every transaction. Norton never forgot a thing. Here was a man whose brain was adept with the skills of both pre-Gutenberg and post-Gutenberg communications. Marshall McLuhan would have loved it!

I hope we'll learn a lot more about John Norton and the role of the First Nations in the War of 1812. So far, most of the narrative upholding the importance of the First Nations has focused on another great leader, Tecumseh.

Perhaps it is because the Shawnee leader figures so huge in the early history of the American Midwest that he has become such a familiar icon. No one can diminish Tecumseh's place in the pantheon of heroes, but there are others who deserve a place alongside him, and one of them is John Norton.

If