Kilmainham Gaol -- a Powerful Symbol

/Last Friday, I took my son, Jacob, and our friend visiting from Canada, Randy, on the guided tour of Kilmainham gaol.

It was one of the first places I had visited on my first trip to Ireland seven years ago. I was deeply impressed with the significance of the place, and how Ireland's Office of Public Works has turned it into a shrine to the leaders of the 1916 Easter Rising who had been been stood up against the wall in the stonebreakers yard and shot by firing squad.

Friday happened to be the 102nd anniversary of four of the executions: Joseph Plunkett, Edward Daly, Michael O'Hanrahan, and William Pearse.

On the prison tour, Joseph Plunkett's story is given particular focus. He had planned to marry his sweetheart, the artist and cartoonist Grace Gifford, on Easter Sunday, but the plans were overtaken by events. Instead, the marriage took place in the prison chapel, and they were given a little time together just hours before his execution.

A few years later, Grace herself was a prisoner at Kilmainham because of her activism on the anti-Treaty side in the Irish Civil War. She painted on the walls of her cell. One of her pictures is still there.

With such threads the Irish have woven their legends and some of their more sentimental rebel ballads.

But on this, my second visit to Kilmainham, my imagination was more occupied with another story from the annals of the prison -- the significance of which I was not aware when I first arrived seven years ago: the fate of Robert Emmet.

Emmet was a 25-year-old student at Trinity College in 1803 when he lead an insurrection against the British. The rebellion fizzled; Emmet was captured and thrown into Kilmainham. The prison had been opened only seven years before. At the time, it was intended as a model of progressive prison reform. Rather than being herded together in a common area, inmates were to be given their own individual cells. That was the theory. In practice, the tiny cells were jammed with as many as five men, while the corridors outside were the living quarters of women and child prisoners. Prisoners slept on damp stone floors -- or on a bit of straw if they could get it. The winter winds whipped through the prison.

One room in this old Georgian portion of the prison has more commodious surroundings, including painted walls, a fireplace, and enough room to move. But these comforts were not intended for the benefit of the prisoner, but for the two guards who were to attend to him on the last night before his execution.

Emmet spent his last night in this room. From a spy hole across from the window, the executioner would look in, unseen. He would gauge Emmet's height and weight and determine how much rope would be required to get the job done the next morning.

At his trial, Emmet's defiant speech provoked the judge to resurrect an old custom: not only would Emmet be hanged as a traitor, his head would be cut off and displayed.

The tour guide explained that among the most memorable lines in Robert Emmet's one-and-a-half hour address to the court following his sentence was the following:

Even though he is considered one of Ireland's great republican martyrs, Robert Emmet's epitaph has not yet been written. No one knows where to erect the head stone. In the tradition of the day, it was up to the family and friends of the executed to retrieve the body for burial. Because Emmet's friends were on the run following the rebellion, and his family wanted to have nothing to do with him, the body and the severed head were buried in an unmarked grave across the road at the pauper's cemetery. Shortly after, the body and head were surreptitiously dug up and removed to a location that remains unknown. Several churches and cemeteries lay claim to be the final resting place of Robert Emmet, but the evidence is inconclusive.

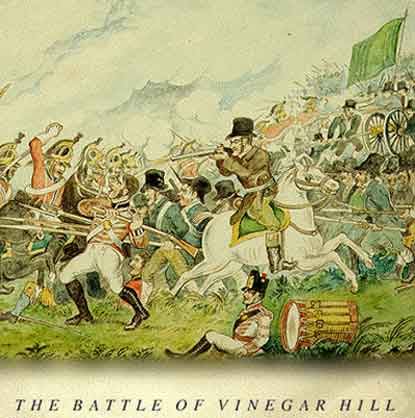

The Emmet story is tied to Jake and Eli's adventures. There is a theory that Robert Emmet was in fact duped into leading the 1803 rebellion. It was a clever ploy to use an idealistic and gullible student leader to flush out remaining supporters of the United Irishman, whose much larger rebellion had been brutally suppressed five years before.

Whether the authorities at "The Castle" were agents provocateurs or whether they were simply brutally efficient in mopping up the aftermath of Emmet's ill-planned and ill-starred uprising, it is likely that one of the principle "villains" in this episode of Ireland's quest for liberty was a senior police official in what today we would call "intelligence." His name was Sir Richard Willcocks.

Sir Richard was the older brother of Joseph James Willcocks who led the Canadian Volunteers in the War of 1812 and is regarded as one of the greatest traitors in Canadian history. In his piece about the Willcocks brothers, a descendant, Richard Henderson, is more knowledgeable about and sympathetic toward Sir Richard than he is to the younger brother, fighting for "liberty" in the colonies.

But one point links the two brothers: in November 1813, Joe Willcocks was given authority on behalf of the occupying American forces to act as the policing authority in Newark (now Niagara-on-the-Lake). It was a task that he went about with relish, scoring revenge on some of his former political opponents. But that is another story -- and a fourth book about matters that take place far away from Kilmainham Gaol.