Alexander Mackenzie -- the Stonemason Prime Minister

/(Originally published in OSCAR)

One of the most important tests of any democracy is how smoothly power can be transferred when governments change. The Dominion of Canada had existed for barely six years when it faced that challenge.

The first general election since Confederation turfed out the scandal-ridden regime of Sir John A. Macdonald and brought in a Liberal government no longer led by George Brown, who had guided them in the crucial years leading to Confederation. The challenge of pulling various Liberal factions into a cohesive first Liberal government fell to Brown’s close friend and chief Lieutenant, Alexander Mackenzie – a man who much preferred to follow than lead.

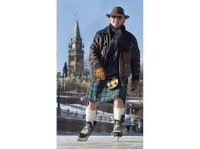

A stonemason whose buildings can still be admired in Kingston, Sarnia and Windsor, Mackenzie guided the young Dominion ably through that first transition and parliamentary crisis. His great-great-grandson, John Morgan, outlined his achievements during a presentation in the series on Canada’s Prime Ministers, organized by the Old Ottawa East Community Association as its Canada150 project.

Morgan has travelled to Scotland to learn more about his ancestor, and his presentation included photographs of Mackenzie’s boyhood home in Logierait, and the many “burgess tickets” awarded to Mackenzie when he returned in triumph as a successful colonial politician. Morgan gave us an insight of the personal life of a self-taught young man who loved the poetry of Rabbie Burns, converted to the Baptist church, emigrated to Canada West with the family of his future bride, and developed a lifelong passion for what we would today call the “progressive” politics of the Scottish Chartists.

In his youth and young adulthood, Mackenzie encountered many tragedies and near tragedies. As a stonemason on the Beauharnois Canal, his leg was crushed by a one-ton block. Twice he fell through the ice of Lake Ontario and almost drowned. He lost 17 members of his stonemason crew when their boat capsized in what is now called Deadman’s Bay. His first wife – his childhood sweetheart – died tragically when a drunken doctor administered too much mercury-based Calomel to treat a fever.

Throughout the adversities, he remained staunchly committed to “reform” ideas, both as a political organizer and newspaper editor. His influence in the Liberal Party derived, in large part, to his sharp, analytical mind, his oratory, and his personal integrity. He persuaded his friend, George Brown, to run for office and organized his campaign. When Mackenzie’s brother declined to run in 1861, the stonemason ran and won in Lambton (Sarnia).

The Liberals of the day had little cohesion. They were a loose amalgamation of “Reformers” under Brown, “Clear Grits” such as William McDougall, and Quebec “Rouges” under Antoine-Aimé Dorion. On the other side of the House, one of Macdonald’s remarkable skills was to cajole, convince and – some might add – corrupt Members of Parliament from all persuasions to join him in forming coalitions.

When Brown quit the Great Coalition in protest in 1865, Macdonald offered Mackenzie the Cabinet post. The stonemason politician feared that, if it chose to dance with Macdonald and the Tories, the Liberal Party would lose its identity. Like Brown, he strongly supported the union of the British North American colonies, but would do so from the Opposition benches.

Brown left politics after his defeat by Macdonald’s Conservatives in 1867. Neither Dorion nor Edward Blake were prepared to assume leadership of the Liberal Party. Mackenzie eventually succumbed to the appeals by his party and became its leader. The Pacific Scandal brought down Macdonald’s government, and following an election, Mackenzie became Prime Minister.

He may have been a reluctant to take on leadership, but there is no denying his accomplishments while in office:

· Creating a modern election system based on Chartist principles, such as secret ballot, same-day elections, and removing property qualifications for MPs;

· Establishing federal institutions including postal services, the Supreme Court, Auditor General, Hansard, and Royal Military College;

· Upholding Canada’s rights as a Dominion within the British Empire;

· Expanding railways, including completion of the Intercolonial Railway, and progress made on survey and construction of the CPR;

· Opening of the West, including the Northwest Territories Act and the Indian Act, and an amnesty negotiated with Louis Riel for his part in the Red River Resistance.

· Laying the foundation for an apolitical and merit-based civil service by not replacing all senior positions with Liberal appointees, and by introducing civil service exams; and

· Reinforcing the supremacy of Parliament and honesty in government.

Mackenzie never sought personal reward nor recognition, and declined three offers of knighthood. He managed to keep his seat in the 1878 election that returned Macdonald to power, and remained an MP until his death in 1892.

He was widely mourned. The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court remembered him as, “the best debater the House of Commons has ever known.” Former Governor General Dufferin remembered a man who was “as pure as crystal and as true as steel, with lots of common sense.”

John Morgan himself summed up Mackenzie’s contribution “a Godfather of Confederation,” who “stepped forward to care for and nurture the young nation.”

The Old Ottawa East series on the Prime Ministers of Canada continues on February 26, when Eddie Goldenberg will speak about his former boss, Jean Chrétien. More speakers will be scheduled in the coming weeks.