150 Years ago, Fenians murdered Ireland's Gift to Canada.

/While in Ireland, I sometimes feel I'm on a mission to explain to the Irish the enormous impact of an Irishman his home country has forgotten. No one here has heard of Thomas D'arcy McGee, Canada's most eloquent Father of Confederation, and Ireland's gift to Canada.

He was gunned down by Fenian assassins 150 years ago tonight. He was returning from a Parliamentary debate that had stretched on past midnight, and was opening the door to the Sparks Street boarding house where he resided when he was shot in the neck.

How can I quickly explain to my Irish listeners why he is so important to Canada -- and why his loss was also a tragedy for Ireland? McGee's place in Canadian history is based upon three contributions.

He was the first to give eloquent voice to Canadian nationalism through his speeches, poems, and journalism. He had an Irishman's gift for words, and it was through words that he helped build a nation.

He called for a "new nationality" that would be neither British nor American, but take the best elements of both. The new nation would be linked by a railway; it would be built through immigration; it would expand into the West; it would develop its industry through protective tariffs. All these ideas became the foundations of Sir John A. Macdonald's National Policy. He said that a separate province could be established for indigenous people in the West. And drawing from his experience as an Irish nationalist, he said that the foundation of a new nation would be a national literature.

Second, he was a Father of Confederation -- that is, one of the politicians who sought to bring together the colonies of British North American into one federation. He had traveled to the Maritime colonies to promote this idea even before the boat arrived in Charlottetown in 1864 with Macdonald, Cartier, Brown, McDougall and the rest -- plus the cases of champagne.

Third -- and this is where it gets interesting for my Irish listeners -- in addition to his vision and his oratory, perhaps his single most important contribution to Confederation was to solve the problems of how to protect minority rights, particularly in education. The balance that Canada found in bringing together English and French, Catholic and Protestant, Maritimers and Central Canadians was regarded at the time as a model for the world.

In Ireland, racked by its own historic turmoil, they would eventually call this "the Canadian solution," and it had some very powerful exponents in the years before the Easter Rising of 1916.

Alas, McGee did not live to lend his passion and eloquence to the cause of Home Rule for Ireland. The Fenians saw to that. They regarded him as a traitor and they murdered him.

But to understand why they felt they needed to get rid of him is to follow McGee's own political journey from radical firebrand to the seeker of compromise. He was descended from rebels of 1798. He grew up in an Ireland where Daniel O'Connell raised enormous crowds to speak on Catholic Emancipation. When he emigrated to the United States at 17, he spoke about the need for Ireland to rise up: "Her people are born slaves, and bred in slavery from the cradle. They know not what freedom is."

By the age of 19, he was the editor of a newspaper calling for support for Ireland's fight for nationality. He urged the United States to take over Canada, "either by purchase, conquest, or stipulation..." He envisioned a "United States of North America" stretching "from Labrador to Panama."

At age 20, McGee returned to Ireland and became involved with the Young Ireland movement of nationalists who promoted Irish identity. The potato blight and famine began to radicalize the movement. No longer willing to rely only on journalism, history and literature to promote Irish national identity, they were inspired by the revolutions across Europe in 1848. McGee was sent to Scotland to raise an armed force to join the liberation.

The campaign fizzled and McGee fled back to the United States, where he issued a public letter denouncing the British. He signed it, "Thomas D'Arcy McGee, A Traitor to the British Government."

But over the following years, McGee's views began to shift profoundly. For one thing, he began to despair of the lack of social cohesion he found in American cities. At the same time, he turned to the Catholic Church to help moderate what he saw as the disorder within American society.

He was looking for a country where minorities could live together in peace, and not be overwhelmed or destroyed by the "nativist" hatreds he found in the United States -- a country that was more open to immigration. He found it north of the border. In 1857, he moved to Montreal.

Within a few short years, the Irish famine had utterly transformed Montreal. At the beginning of 1847, with a population of about 50,000, Montreal was already the largest city in British North America. That year, 100,000 Irish refugees disembarked at the quarantine station at Grosse Isle, and of those, some 70,000 moved on up the St. Lawrence to Montreal. It's hard to imagine a similar phenomenon. What if, for example, five million starving Syrian refugees -- many of them diseased and dying-- arrived in Montreal today? Would we welcome them the way the Montrealers did in 1847?

But Montrealers of the day did reach out to the Irish refugees. They built ventilated sheds along the river to shelter them. "Nuns, priests, Protestant clergy and others disregarded their own safety to care for the newcomers," says Marian Scott in a recent issue of the Montreal Gazette. "The Mohawks of Kahnawake brought food for the starving strangers."

The generosity and compassion Montrealers had shown to his countrymen obviously had an impact on McGee. He made Montreal his home, began studying law at McGill, and started to rethink his position on the meaning of liberty.

“To the American citizen who boasts of greater liberty in the States, I say that a man can state his private, social, political and religious opinions with more freedom here than in New York or New England. There is, besides, far more liberty and toleration enjoyed by minorities in Canada than in the United States.”

In addition to studying law, McGee resumed his journalism, poetry and work on popular histories. He took an active part in politics, and was soon recognized as someone who could deliver the Irish vote in Montreal and elsewhere to whatever party could woo his support.

Political parties and identities were not as set as they've become today. It was common for politicians to move among the various parties, seeking the one that would advance their personal platforms and ideas. In 1857, McGee was elected as a Rouge to represent Montreal in the Legislative Assembly. He supported the short-lived government of the Reformer, George Brown, and in Opposition, fought against the Bleu/Tory coalition of Cartier and Macdonald.

McGee broke with Brown when the Globe attacked the Irishman's ideas on school policy. In 1862 he was asked to become president of the council in John Sandfield Macdonald's administration of moderate Reformers. He was dropped from cabinet in favour of Antoine-Aime Dorion, who opposed McGee's position on railways. In the 1862 election, John S. Macdonald ran a candidate to oppose McGee, but McGee won, along with two Conservatives. It was in this way that McGee completed his migration to the Tories he had once reviled.

As a Conservative, he became minister of agriculture, immigration and statistics. He participated in the 1864 conferences that took place in Charlottetown and Quebec City. It was he who introduced a resolution guaranteeing the education rights of religious minorities in Canada East (Quebec) and Canada West (Ontario).

But while McGee was becoming more conservative in his politics, much of the Irish community in Canada and the United States were becoming more radicalized. The Irish Republican Brotherhood (or Fenians) emerged from the American Civil War as a powerful movement to strike a blow for Ireland by attacking British colonies in North America.

McGee opposed the Fenians in Canada, and in 1865 he returned to Ireland to denounce them in a speech he made in his boyhood home of Wexford. It was a speech that gained a lot of attention on both sides of the Atlantic, and it eroded his political support among the Irish in Canada.

The St. Patrick Society of Montreal, which had invited him to come to Canada to run in Montreal ten years before, expelled him from its membership and nominated its own candidate. McGee won the 1867 election nonetheless, but it was clear that he could no longer deliver the Irish vote.

He'd had enough of politics. He wanted out. John A. Macdonald promised him a civil service post which would give him what he had never enjoyed: a secure income from where he could continue his literary endeavours.

But we'll never know what McGee might have produced in his maturity, or how he would have used his intellect and his passion to help shape what would soon emerge as the Home Rule movement in Ireland.

Why did they kill him? He was a voice for reason and moderation at a time when the Fenians were calling for rebellion and violence. He passionately and articulately made the case for how a constitutional monarchy could put a check on the chaos and corruption that characterized America at the time. He showed that there was a moderate way out of Ireland's problems, and such ideas the Fenians would not abide in their quest for victory through warfare.

But in making this case to my Irish listeners, I also have to add a caveat: if the British had treated the French in North America as abysmally as they had treated the Catholics in Ireland, ideas such as McGee's may not have taken root in Canada.

An Irish immigrant named Patrick James Whelan was convicted and hanged for the murder, although it's still open to question whether he pulled the trigger. Pierre Brault explores the controversy in his one-man theatre piece, "Blood on the Moon." Jane Urquhart does a marvelous job of using magic realism to recreate the world of Irish immigration, and McGee's role, in her novel, Away. David A. Wilson's two-volume biography, subtitled Passion, Reason and Politics, 1825-1857 and The Extreme Moderate, 1857-1868 have become the definitive sources.

McGee's contribution to Canada -- as Father of Confederation, champion of minority rights, and as the first voice for a Canadian national identity -- are inestimable. His murder was widely mourned In Montreal, out of a city of 105,000, some 80,000 honoured him when he was laid to rest at Notre-dame-des neiges cemetary.

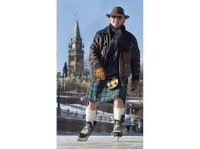

Today, his name is widely known in Canada. There's a Thomas D'arcy McGee building near the spot where he was murdered, and down the street, a pub named D'arcy McGee's is a favourite watering hole for Parliament Hill staff. If there's one thing that Canadians know about him, it's probably that he was murdered. His poetry and journalism is no longer read, but his impact as a champion of Canadian literature was enormous for the generation growing up at the time of Confederation.

But among today's Irish, he's unknown. Some are taking steps to remedy that. Canada's former ambassador to Ireland, Loyola Hearn, helped develop the Thomas D'arcy McGee Foundation and an interpretive centre in Carlingford, where McGee was born. The interpretive centre has an exhibition, "Thomas D'arcy McGee; Irish Rebel -- Canadian Patriot." Each year the Foundation hosts a summer school that uses McGee's life, career and ideas to link Irish and Canadian issues.

The world needs more of Canada? Maybe. But Ireland needs more D'arcy McGee? Yes, I think so.